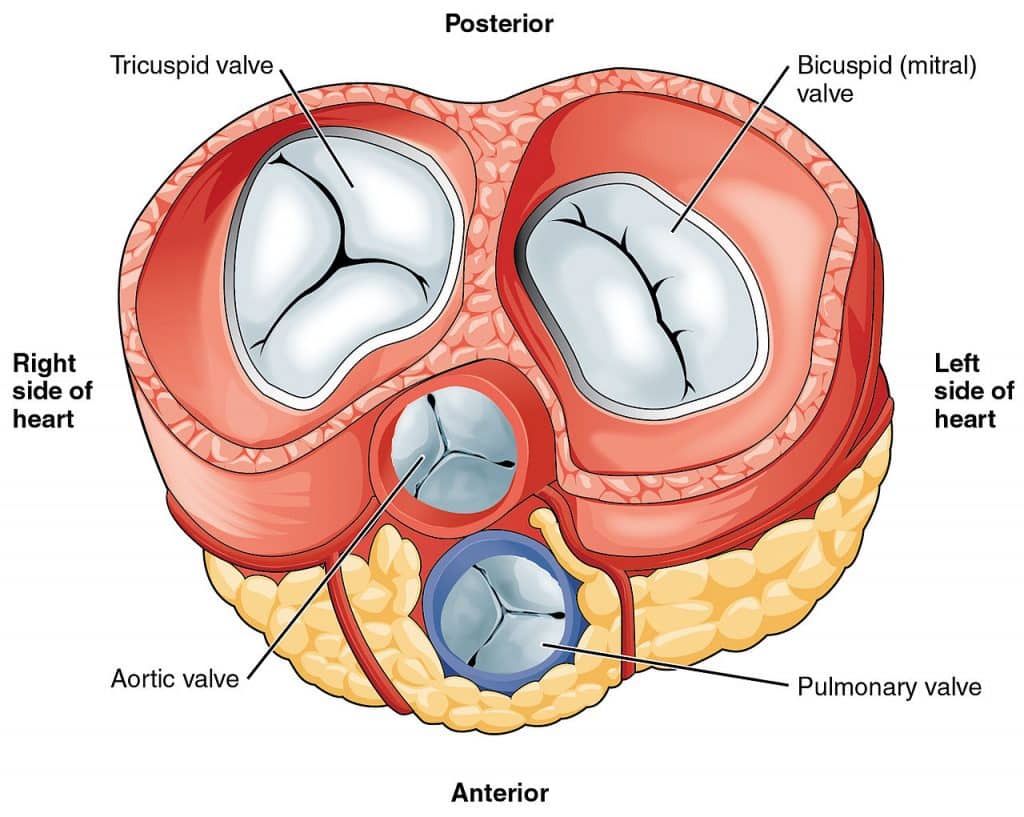

There is only one place in the human body with three duplicate heart valves, called the tricuspid valve. The valves of the heart are structures which ensure blood flows in only one direction. They are composed of connective tissue and endocardium (the inner layer of the heart).

There are four valves of the heart, which are divided into two categories:

- Atrioventricular valves: The tricuspid valve and mitral (bicuspid) valve. They are located between the atria and corresponding ventricle.

- Semilunar valves: The pulmonary valve and aortic valve. They are located between the ventricles and their corresponding artery and regulate the flow of blood leaving the heart.

What does the tricuspid valve do?

The heart pumps blood in a specific route through four chambers (two atria and two ventricles). Every time your heart beats, the atria receive oxygen-poor blood from the body. And the ventricles contract (squeeze) to pump blood out.

As the heart pumps, valves open and close to allow blood to move from one area of the heart to another. The valves help ensure that blood flows at the right time and in the correct direction.

The tricuspid valve ensures that blood flows from the right atrium to the right ventricle. It also prevents blood from flowing backward between those two chambers. When the right atrium fills, the tricuspid valve opens, letting blood into the right ventricle. Then the right ventricle contracts to send blood to the lungs. The tricuspid valve closes tightly so that blood does not go backward into the right atrium.

What is the tricuspid valve made of?

The tricuspid valve is made of three thin but strong flaps of tissue. They’re called leaflets or cusps. The leaflets are named by their positions: anterior, posterior and septal. They attach to the papillary muscles of the ventricle with thin, strong cords called chordae tendineae.

With every heartbeat, those leaflets open and close. The sounds of the heart valves opening and closing are the sounds you hear in a heartbeat.

Does the heartbeat in 3/4 time?

Yes, the heart is closer to 3/4 time than 4/4 time. The waltz is in perfect synch with the heartbeat. Any music slower than the heartbeat tends to relax us, and any music faster than the heartbeat excites.

RadioLab | Our Little Stupid Bodies

There was a lively discussion about how body parts evolved on January 12, 2024 Episode: Our Little Stupid Bodies, question 4. Hear the recording and read the transcript below (permission to post from RadioLab).

Recording | Our Little Stupid Bodies

Transcript of question 4

LULU: Biggest thanks—and apologies, I guess—to our producer Becca Bressler. And that will do it for our show of stupid questions about our stupid bodies.

LATIF: Not quite.

LULU: What? What? Those were three acts.

LATIF: I know we—I know we said we’d do three, but I got one more little—little Magic Bus ride journey here.

LULU: [laughs] Latif, your little brain—your little brain can’t rest. Okay, what is it?

LATIF: No. And this is from actually an even littler brain than mine. This is from my son, my older son.

FIVEL NASSER: My name is F-I-V-E-L.

LULU: Oh!

LATIF: His name is Fivel.

FIVEL NASSER: I work at a Fivel factory, where we make Fivels …

LATIF: So a while back …

FIVEL NASSER: I have a question.

LATIF: … he’d asked me this question that just completely stopped me in my tracks.

FIVEL NASSER: Is there anything in our bodies that we have three of?

LULU: [gasps]

LATIF: We have one nose, we have two eyes, we have four limbs, we have five fingers on a hand.

LULU: Like, twelve ribs.

LATIF: Yeah.

LULU: Are there any threes?

LATIF: Are there any threes in our body?

LULU: Are there?

LATIF: Well, just—just in that initial moment, like, when he asked me that, I was like, “Oh my God, I have no idea.” And then I started talking to a bunch of people. I started talking to friends and doctors, and one of the first answers that I got from people—like, one of my friends was like, “I have three nipples!”

LULU: Oh!

LATIF: Or, like, some people are born with three kidneys or something like that.

LULU: Oh, really?

LATIF: Yeah, but …

LULU: Some people have three—my uncle has three nipples!

LATIF: Yeah, so—but I was like, okay, that’s—that’s not the normal way things go.

LULU: So there’s—you’re saying there’s accidental …

LATIF: There’s sort of accidental threes, but then the thing I was looking for is kind of most or all of us should—should have three of this thing.

LULU: Okay.

LATIF: And at that point I was just like, I can’t think of anything.

DIANE KELLY: Okay.

AVIR: Hmm.

DIANE: Three of …

AVIR MITRA: So let me think about that.

LATIF: So I called up a few friends of the show.

AVIR: It’s a great question.

LATIF: ER doctor and reporter, Avir Mitra, and …

DIANE: Um, it’s …

LATIF: … our fact-checker Diane Kelly, who also happens to have a PhD in comparative anatomy.

DIANE: Almost everything comes in twos.

AVIR: Because we’re so symmetrical, you know?

DIANE: Or you have one thing.

AVIR: But not completely symmetrical. I mean, I’m struggling here, but …

LATIF: But I was like, there’s gotta be something. There’s gotta be a trio somewhere.

LULU: Right? It really does feel like there—like, I feel like there’s one on the tip of my tongue, but I’m not talking about taste buds. But, like …

AVIR: I gotta keep thinking.

LULU: Uh …

DIANE: Well, female mammals have three exits to their reproductive, and …

LATIF: Okay.

DIANE: … waste systems.

LATIF: Okay, okay, okay.

DIANE: But only females.

LATIF: Only females, right.

DIANE: In mammals, in ears, the inside of each ear has three bones.

LATIF: But then that’s tricky, because it doesn’t quite …

DIANE: They’re each—they’re each a different bone. It’s a chain of three bones, but they’re each a different bone.

LULU: Oh, that’s a cheat.

LATIF: It feels like a cheat. Those three are different from each other.

DIANE: Yes.

LULU: That’s a cheat.

LATIF: They’re not the same.

DIANE: They are not the same.

LATIF: They’re not the same.

DIANE: No, they are not the same.

LATIF: What I want is I want three discreet—three of the same thing.

LULU: So you want a set. Three little eyeballs.

LATIF: Yeah. Yeah.

LULU: You want three …

LATIF: Yeah.

LULU: I feel you. Three hearts. You want that.

DIANE: Three same things.

LATIF: Right.

AVIR: Ooh, I’ve got a good one that’s three, but it’s kind of gross.

LATIF: Okay, go for it.

AVIR: There’s three spongy parts that make up the sponginess of the penis, you know, that fill up with blood.

LATIF: Okay.

DIANE: Yes, there are three erectile bodies in the penis.

AVIR: Two of them are called the corpus cavernosum. And then one is called the corpus spongiosum.

DIANE: Which is underneath the two of them. And then it flares out of the—at the far end of the penis and forms the glans tissue.

AVIR: So there’s three.

DIANE: But there are different—there’s one pair of one kind of erectile body and then there’s a third of another type of erectile body.

LATIF: Okay. Okay, so that’s not gonna cut it.

DIANE: So it—it kind of—it’s kind of a non-starter.

LATIF: Also that’s only half the population anyway.

AVIR: Okay—ooh, okay, I got another one. Do you know that we have a third eye?

LATIF: Tell me, where’s our third eye?

AVIR: It’s actually, like—when you look at, like, religious drawings, you know, and, like …

LATIF: Right?

AVIR: It’s, like, where they’re talking about. It’s kind of in the center of your head.

LATIF: Okay.

AVIR: Most likely, that was a very old, old eye, back when we didn’t even have skulls and we weren’t even human.

LATIF: Really? So it’s like a vestigial eye kind of thing?

AVIR: I’m just gonna go out on a limb and say yes.

LATIF: Okay.

DIANE: He’s thinking of the pineal gland. It’s—in us, it’s, like, way deep in the brain, but it’s not like our eyes.

LATIF: Okay. So you call BS on that one?

DIANE: I don’t think it—I don’t think it matches your parameters.

LULU: Nah, that doesn’t count. That doesn’t count.

LATIF: Right. And I just kept asking more and more people. Like …

LATIF: … in the body that we have three of.

DANIELLE REED: Hmm.

LATIF: Like, I was in an interview—completely unrelated interview with Danielle Reed. She’s an expert on senses and the brain.

DANIELLE REED: Yeah, I can’t think of a thing.

LATIF: And I asked her the question.

DANIELLE REED: No, I can’t think of anything.

LATIF: She was stumped. And then I went to Cat Bohannon.

CAT BOHANNON: I’m Cat Bohannon. I’m a researcher and an author, just finished my PhD at Columbia University in the evolution of narrative and cognition.

LULU: Okay.

LATIF: Just wrote a book called Eve: How the Female Body Drove 200 Million Years of Human Evolution.

LULU: Oh, neat! I was just hearing about this book.

LATIF: Yeah, so I asked her a question that had nothing to do with the book.

CAT BOHANNON: Oh, I thought you were gonna ask me something about genitals.

LATIF: Oh yeah.

CAT BOHANNON: Because, like, half of my life right now is answering …

LATIF: So when I asked her the three body part question, she said …

CAT BOHANNON: You’re—you’re very unlikely to arrive at a three. So actually, very good question.

LATIF: But why is it so hard to find threes in the body? Because I mean, like, I found a four, I found a five, I found a six. It feels easier to find every other number besides three.

CAT BOHANNON: In part that is because bodies are things which are built, actually.

LATIF: So according to Cat, because bodies are built, they need a building plan, and that plan needs to be effective, but it also needs to be efficient.

CAT BOHANNON: If you’re thinking about how this body plan is building out, you—you can simply think of each half of the body essentially doing the same thing in a mirror function.

LATIF: Which means that for basically all animals, symmetry is the baseline move. It’s efficient, because you have to just plan half of something and then you say, “Double it.” It’s good for moving around, right? Think of walking, crawling. Being symmetrical really helps. And also because it gives you a backup.

CAT BOHANNON: The central reason that most of us have two testicles, two ovaries, two things, is also that well, if one fails, we’re still good.

LATIF: Now of course, there are times when you want to break the pattern.

CAT BOHANNON: But it’s often a shrinking from two to one. There may be something about having two hearts that would be deeply stupid. You know, this is simply better to build as a single unit, a single pump, as it were, to just push this through the system than to try to maintain two because then you’d have to coordinate the two. It would be like this weird waltz—well, maybe not a waltz. It would probably be a four-four. But you know what I mean, right?

LATIF: And the other reason you might go from two to one is …

CAT BOHANNON: Running the thing.

LATIF: … the simple matter of the cost.

CAT BOHANNON: You know, how much energy is it gonna take to maintain this thing, to run this thing, to use this thing? I’m not at all surprised we don’t have two brains. That is the most metabolically expensive tissue in our body.

LATIF: It feels like over the evolution of the human body, it’s like the number one and the number two sort of arm-wrestled over every part of the body. It would be like, “Should we have one of these? Should we have two of these? Should we have one of these? Should we have two of these?”

CAT BOHANNON: Effectively. Effectively.

LATIF: And then number three is not even at the table. Number three is like, “Hey I got a great idea! We could do three!” And everyone’s like, “No. No.”

CAT BOHANNON: Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes.

DIANE: Three is not a magic number when it comes to animal bodies.

LATIF: Huh!

DIANE: [laughs]

LATIF: But then …

AVIR: Whew! I just, like, ran home so I could set this up.

LATIF: Avir called me back.

LULU: I can picture this getting so under his skin. Like …

LATIF: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Oh, it really bugged him.

AVIR: I was just in bed at night and it just—like, the answer just came to me.

LATIF: So what is it?

AVIR: Okay. So basically, the aortic valve, which is the only way to get blood from your heart to the rest of your body, you gotta go through a valve. It’s called the aortic valve. And that valve, the best design is for it to have three cusps.

LATIF: The design that makes sure blood goes one way out the heart and not the other way back in, because that would be very bad.

AVIR: They’re triangle doors that, like, open up when you want the blood to go out, and then just flop back down when you want it to close. But actually what it is is, like, three leaflets.

LATIF: What do you mean by leaflets?

AVIR: Like, three triangular doors that add up to being a circle. Like, if you saw a Mercedes Benz symbol, it would be those three—the up, left—almost like a peace sign, you know? Like, that type of thing.

DIANE: Yeah, so that’s—that’s a possibility, because there’s three cusps, and they’re all the—they’re all the same. That’s true. That’s a good—that’s a good option. But there’s more than one of them.

AVIR: Okay, so the—but the—yeah, this is where my whole thing may break down. You have more valves.

LATIF: Oh, no. You didn’t just—no way! No way! That doesn’t count!

AVIR: [laughs] No, no, but listen. No! Listen, listen. You have four chambers of the heart.

LATIF: Four chambers. Each have a valve. Four valves.

AVIR: Yeah.

LATIF: And so then I was like, oh, but that kind of means we have 12 cusps.

LULU: [laughs]

LATIF: Not three. And then it got even weirder, because he was like, “No, no, no, because one of those valves is not a tricuspid valve. It’s a bicuspid valve, so we have two.” So I was like, “11?

LATIF: Like, we found an 11?

AVIR: We found an 11.

LATIF: And we still haven’t found a three?

AVIR: No, we found a three.

LATIF: I don’t—that’s an 11.

AVIR: Damn it!

LATIF: But I did—I did end up deciding to take it to Cat anyway to see what she thought.

CAT BOHANNON: I forgot about that!

LATIF: Do you feel like that—does that cut it for you? Does that feel like—does that feel good?

CAT BOHANNON: You know, it had—I got a little tingle. I got a little something. I got a little something thinking about it.

LATIF: Okay.

CAT BOHANNON: But keep going, because you were about to tell me why not.

LATIF: Because there are …

LATIF: And I explained my whole thing to her. Like, isn’t this actually—like, it looks like a three, but this is actually an 11, right?

CAT BOHANNON: Technically 11 cusps. However, three would share the property of having the three cusps.

LATIF: If you don’t count the cusps, if you count instead the tricuspid valves …

LULU: Oh, there are three tricuspid valves?

LATIF: There are three tricuspid valves.

CAT BOHANNON: Three sets of three, which feels satisfying and vaguely mystical.

LATIF: Three threes, literally in your beating heart.

LULU: Oh! That’s beautiful!

LATIF: Okay, all right. There we go. There we go. Three threes.

LULU: Did you—did you tell Fivel? Is he excited?

LATIF: Yeah, yeah. I got him on mic. I explained the whole thing.

LATIF: Okay, my buddy. My buddy.

FIVEL NASSER: What?

LATIF: There’s little doors in your heart, they’re shaped like a little pizza with three slices. I laid it out for him.

LATIF: So there’s this special door in your heart.

FIVEL NASSER: Heart things.

LATIF: Three heart things.

FIVEL NASSER: Heart doors.

LATIF: Three heart doors. And then in the door …

FIVEL NASSER: It goes …

LATIF: Yeah?

FIVEL NASSER: There’s three of them, and it’s three threes which make nine of them.

LATIF: Yeah. Three of these kinds of doors, with three flaps in each of them.

FIVEL NASSER: Whoa!

LATIF: So you think that doesn’t count?

FIVEL NASSER: Yeah.

LATIF: But there’s three of them.

FIVEL NASSER: Okay, fine.

LATIF: [laughs]

FIVEL NASSER: [laughs]

LATIF: So I found you a three in the body.

LATIF: Okay. Okay that actually was our last Magic School Bus trip.

LULU: So, you know, go back to your—go back to your life.

LATIF: Your desk, bus is parked. You can go back to your normal school or work day.

LULU: You know, go learn about the Krebs cycle. But don’t worry, because we actually have another wild ride coming up in just two weeks. Latif, this is a story of yours that has captured your heart and sent you—basically put jet—jet—jet engines on the school bus and launched your all the way into space.

LATIF: True!

LULU: So we are all gonna get to hear that. I’m very excited for it.

LATIF: In the meantime, this episode was reported by myself, as well Molly Webster, Alan Goffinski and Becca Bressler.

LULU: And it was produced by Sindhu Gnanasambandan, Molly Webster and Becca Bressler. With help from Matt Kielty, Ekedi Fausther-Keeys and Alyssa Jeong Perry.

LATIF: With music and sound design from Jeremy Bloom and mixing help from Arianne Wack.

LULU: Original song from Alan Goffinski, with back up by his wife Alina Goffinski. Special thanks to Mark Krasnow, Kari Leibowitz and Andrea Ebbers.

LATIF: Thank you for listening.

LULU: Bye!

[LISTENER: Radiolab was created by Jad Abumrad and is edited by Soren Wheeler. Lulu Miller and Latif Nasser are our co-hosts. Dylan Keefe is our director of sound design. Our staff includes: Simon Adler, Jeremy Bloom, Becca Bressler, Ekedi Fausther-Keeys, W. Harry Fortuna, David Gebel, Maria Paz Gutiérrez, Sindhu Gnanasambandan, Matt Kielty, Annie McEwen, Alex Neason, Sarah Qari, Alyssa Jeong Perry, Sarah Sandbach, Arianne Wack, Pat Walters and Molly Webster. Our fact-checkers are Diane Kelly, Emily Krieger and Natalie Middleton.]

[LISTENER: Hi, I’m Erica in Yonkers. Leadership support for Radiolab’s science programming is provided by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, Science Sandbox, a Simons Foundation initiative, and the John Templeton Foundation. Foundational support for Radiolab was provided by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.]

-30-

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of programming is the audio record.