The three-strikes law significantly increases the prison sentences of persons convicted of a felony who have been previously convicted of two or more violent crimes or serious felonies, and limits the ability of these offenders to receive a punishment other than a life sentence.

The three-strikes law significantly increases the prison sentences of persons convicted of a felony who have been previously convicted of two or more violent crimes or serious felonies, and limits the ability of these offenders to receive a punishment other than a life sentence.

Under the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, the “Three Strikes” statute (18 U.S.C. § 3559(c)) provides for mandatory life imprisonment if a convicted felon:

been convicted in federal court of a “serious violent felony” and has two or more previous convictions in federal or state courts, at least one of which is a “serious violent felony.” The other offense may be a serious drug offense.

The statute goes on to define a serious violent felony as including murder, manslaughter, sex offenses, kidnapping, robbery, and any offense punishable by 10 years or more which includes an element of the use of force or involves a significant risk of force.

The State of Washington was the first to enact a “Three Strikes” law in 1993. Since then, more than half of the states, in addition to the federal government, have enacted three strikes laws. The primary focus of these laws is the containment of recidivism (repeat offenses by a small number of criminals). California’s law is considered the most far-reaching and most often used among the states.

Three strikes laws have been the subject of extensive debate over whether they are effective. Defendants sentenced to long prison terms under these laws have also sought to challenge these laws as unconstitutional. For instance, one defendant was found guilty of stealing $150 worth of video tapes from two California department stores. The defendant had prior convictions, and pursuant to California’s three-strikes laws, the judge sentenced the defendant to 50 years in prison for the theft of the video tapes. The defendant challenged his conviction before the U.S. Supreme Court in Lockyer v. Andrade (2003), but the Court upheld the constitutionality of the law.

Source: http://criminal.findlaw.com/criminal-procedure/three-strikes-sentencing-laws.html

Primer: Three Strikes – The Impact After More Than a Decade

Introduction

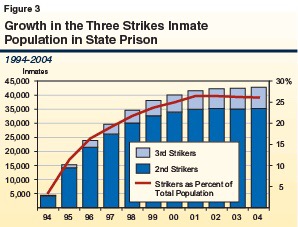

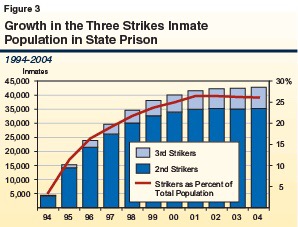

In 1994, California legislators and voters approved a major change in the state’s criminal sentencing law, (commonly known as Three Strikes and You’re Out). The law was enacted as Chapter 12, Statutes of 1994 (AB 971, Jones) by the Legislature and by the electorate in Proposition 184. As its name suggests, the law requires, among other things, a minimum sentence of 25 years to life for three-time repeat offenders with multiple prior serious or violent felony convictions. The Legislature and voters passed the Three Strikes law after several high profile murders committed by ex-felons raised concern that violent offenders were being released from prison only to commit new, often serious and violent, crimes in the community.

In this piece, we summarize key provisions of Three Strikes and You’re Out; discuss the evolution of the law in the courts; estimate the impact of the law on state and local criminal justice systems; and evaluate to what extent the law achieved its original goals. Our findings are based on analysis of available data, review of the literature on Three Strikes, and discussions with state and local criminal justice officials.

Background

The Rationale for Three Strikes. Repeat offenders are perhaps the most difficult of criminal offenders for state and local criminal justice systems to manage. These offenders are considered unresponsive to incarceration as a means of behavior modification, and undeterred by the prospect of serving time in prison. For this reason, longer sentences for this group of offenders have a strong appeal to policy makers and the public. Supporters of Proposition 184 argued that imposing lengthy sentences on repeat offenders would reduce crime in two ways. First, extended sentences, also referred to as sentence enhancements, would remove repeat felons from society for longer periods of time, thereby restricting their ability to commit additional crimes. Second, the threat of such long sentences would discourage some offenders from committing new crimes.

Key Features of Three Strikes. The Three Strikes law imposed longer prison sentences for certain repeat offenders, as well as instituted other changes. Most significantly, it required that a person who is convicted of a felony and who has been previously convicted of one or more violent or serious felonies receive a sentence enhancement. (Figure 1 defines several important terms in criminal sentencing law.) The major changes made by the Three Strikes law are as follows:

Second Strike Offense. If a person has one previous serious or violent felony conviction, the sentence for any new felony conviction (not just a serious or violent felony) is twice the term otherwise required under law for the new conviction. Offenders sentenced by the courts under this provision are often referred to as “second strikers.”

Third Strike Offense. If a person has two or more previous serious or violent felony convictions, the sentence for any new felony conviction (not just a serious or violent felony) is life imprisonment with the minimum term being 25 years. Offenders convicted under this provision are frequently referred to as “third strikers.”

Consecutive Sentencing. The statute requires consecutive, rather than concurrent, sentencing for multiple offenses committed by strikers. For example, an offender convicted of two third strike offenses would receive a minimum term of 50 years (two 25-year terms added together) to life.

Unlimited Aggregate Term. There is no limit to the number of felonies that can be included in the consecutive sentence.

Time Since Prior Conviction Not Considered. The length of time between the prior and new felony conviction does not affect the imposition of the new sentence, so serious and violent felony offenses committed many years before a new offense can be counted as prior strikes.

Probation, Suspension, or Diversion Prohibited. Probation may not be granted for the new felony, nor may imposition of the sentence be suspended for any prior offense. The defendant must be committed to state prison and is not eligible for diversion.

Prosecutorial Discretion. Prosecutors can move to dismiss, or “strike,” prior felonies from consideration during sentencing in the “furtherance of justice.”

Limited “Good Time” Credits. Strikers cannot reduce the time they spend in prison by more than one-fifth (rather than the standard of one-half) by earning credits from work or education activities.

Read more http://www.lao.ca.gov/2005/3_strikes/3_strikes_102005.htm