Posted March 16th, 2011 at 2:00pm in First Principles

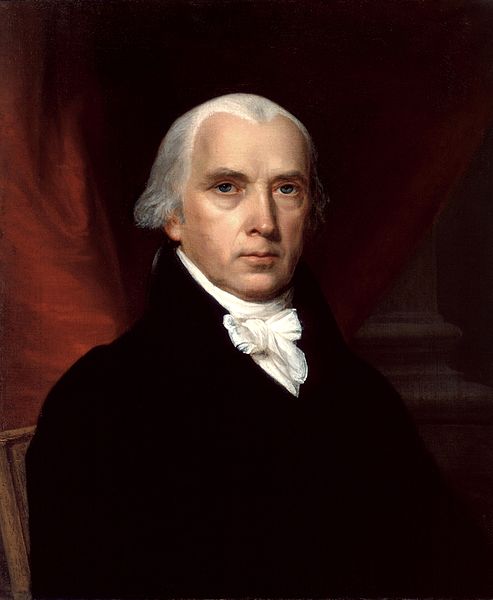

If forced to enter a duel with a Founder, James Madison would be an easy opponent—slender, diminutive, and painfully shy. But if you were to engage in any sort of intellectual debate with “little Jimmy,” you would indeed suffer a cerebral defeat. Today we celebrate Madison’s birthday, and though he is not with us, his Constitution still stands.

If forced to enter a duel with a Founder, James Madison would be an easy opponent—slender, diminutive, and painfully shy. But if you were to engage in any sort of intellectual debate with “little Jimmy,” you would indeed suffer a cerebral defeat. Today we celebrate Madison’s birthday, and though he is not with us, his Constitution still stands.

In May of 1787, Madison arrived at the Constitutional Convention having read scores of books about political philosophy, the rise and fall of empires, and enlightenment thought. For four summer months, Madison tirelessly explained and defended his “Virginia Plan” to the other delegates. At the same time, Madison also understood the art of compromise, and like any tactful politician, he was willing to concede some points to the North and to the South in order to complete a draft of the Constitution.

On September 17, 1787, while the members signed the Constitution, Benjamin Franklin remarked that painters had often found it difficult to distinguish in their art a rising from a setting sun. Franklin’s reflection about whether the signing of the Constitution marked the beginning or end of the republic spurred Madison to answer the question as clearly as possible. He was so determined to explain the strengths and benefits of the Constitution that he drafted a series of essays, later published as the Federalist. In these essays, he analyzed the ways the Constitution protects against both forms of tyranny: on one end, popular factions undermining government and on the other, government oppressing the people.

Though Madison’s moments of brilliance still guide constitutional government, his presidency reveals some of the challenges he faced. He was a quiet man—one who dreaded public speaking and never could measure up to the other dashing Virginians: Washington, Jefferson, Henry and the like. It was often remarked that his wife, Dolly, played such an integral role in welcoming and entertaining guests that he never could have won the presidential election without her. As president, he declared war on Britain in the War of 1812, which caused much economic and political strife that might have been avoided. He also created the Second Bank of the United States and proposed a standing army, two policies he had opposed earlier on in his career. Yet, ultimately, Madison firmly protected the constitutional framework, vetoing the Bonus Bill—which funded infrastructure that was under the states’ jurisdiction—because of its constitutionally dubious grounds. These decisions demonstrate that Madison himself had to wade through circumstances that were not specifically addressed in the Constitution.

On Madison’s birthday, we celebrate the legacy of a man who embodied both the exceptional talent and the ordinary struggles of a statesman. So as we commemorate his birthday, we offer up three cheers to Madison—one for his success in drafting the Constitution, another for his air-tight defense of it in the Federalist, and finally, a last hooray for his adherence to the Constitutional framework despite tenuous circumstances.

Brittany Baldwin is currently a member of the Young Leaders Program at the Heritage Foundation. For more information on interning at Heritage, please visit: http://www.heritage.org/about/departments/ylp.cfm