The Rule of Three multiplies effect of speech and humor

If you want to talk funny, timing is everything.

Comic timing is one of those things all comedians and humorists insist is necessary to the successful performance of humor. But nobody seems to be able to explain exactly what comic timing is.

After extensive research and study, I have concluded comic timing is not just one simple rule or formula the budding humor practitioner must master. It’s more likely a number of things.

What humorist Doc Blakely calls “The Rule of Three” is part of the formula.

“It is generally accepted in humor that one general theme is overworked after it has been attacked at least three times with punch lines that are quite similar,” Blakely writes.

He says it applies to one-liners and jokes alike. Save the strongest of the three jokes for last, he advises, adding you might want to intentionally use a weak or mediocre joke as the first in the triplet to make the last one seem stronger.

With Blakely’s wisdom in mind, notice how many funny stories use a different kind of “Rule of Three.” Many stories have you heard start out, “There was a priest, a minister and a rabbi … .” Three characters seems to work well when you are populating your own stories to make them funnier.

Comedy professor and author Melvin Helitzer claims there’s something magic about the number three. Calling them triples, he cites a series of three examples or three alternative solutions offered consecutively. Helitzer thinks of them as jokes on the way to a joke or firecrackers on the way to a big blast.

He points out the Bible is filled with triples, such as the three wise men, the Trinity and others.

Three words of description work well in introducing characters. Or three actions listed consecutively are more effective in building the tension good punch lines depend on than just one or two. Whether it’s descriptive words or actions, four always seems to be too many, slowing your story down, and two not enough.

Helitzer recommends no less than three examples, no more than three stories in a sequence on one subject and no more than three minutes on any one theme. To sustain what’s called a “roll,” he says, “you must build one topper on another — with a minimum of three.”

As an example, Helitzer offers, “My wife’s an angel. She’s constantly up in the air, continually harping on something and never has anything to wear.”

You can see how Helitzer’s triples maintain tension and build the story toward its unexpected logical resolution.

Although I haven’t been able to find written references to it, there is what I think of as a musicality to a well-spoken phrase or sentence. That is particularly true with one-liners, as well as punch lines on longer stories.

As an example, look at what arguably has become the most famous punch line in the English language, the late Henny Youngman’s “Take my wife. Please.” Listen to the words in your head. Pay attention to the rhythm created by the emphasis on words and using a pause, which is called a beat. “Take my wife. (beat) Please.”

Emphasis on alternating words, and syllables in longer words, gives it the proper rhythm. The pause, or beat, serves two purposes. It fits the rhythm you want to establish, and it builds tension before revealing the surprise finish that completes the logic.

If you are musically inclined, you might think of each of the first three syllables being a quarter-note in a measure. The beat is a quarter-note rest. The final word in the sequence, “Please,” is a half-note, followed with at least a half-note pause to wait for laughter.

Experiment with the delivery of punch lines in your favorite stories. Sometimes switching words around creates a more effective, funnier rhythm. If you have trouble, look for synonyms or find new ways to express the surprise ending that have a better rhythm.

Not all rhythms suitable to humor have the simple la-DEE-la-DEE pattern. Go back to the Henny Youngman example and activate the setup line that is seldom remembered or used.

Here’s the way it goes: “Women are crazy today.” The rhythm is DEE-DEE-la-DEE-DEE, followed my a silent beat. Next comes the punch line, “Take my wife. Please.” DEE-la-DEE, la-DEE. The rhythm changes in the middle of the joke.

Melvin Helitzer’s recommended cadence is da-da-Tah-da-da-Tah-dah-dah-TA, three groups of three syllables. The important thing is that you establish a rhythm to build and deliver on.

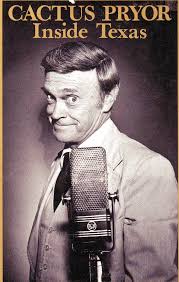

The importance of rhythm came home to me years ago when I watched humorist Cactus Prior deliver lines. He patted his foot in a four-four beat like a musician playing or a conductor leading. The result: the delightful music of laughter, when and where conductor Cactus led his orchestral audience to come in like a brass section for their part in a successful performance.

ELLIS POSEY is a professional humorous speaker and author. Contact him at 863-5938 or visit his Web site at (http://www.ufindm.com/funnyside).