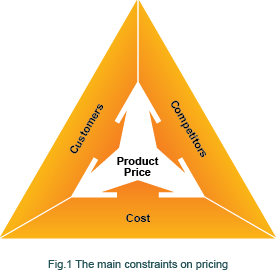

This article gives you guidelines on how to price your products and the typical process used in most companies. At a basic level the main constraints on pricing are the costs associated with your offer, customers’ willingness to pay and your competition (see Fig.1). Product costs set a lower limit below which prices are not viable in the long term. The upper limit is a combination of affordability for your target customers, how they perceive the value of your product and how it compares to the alternatives eg. your competition.

Choosing a pricing strategy

There are three basic pricing strategies. Marketing skimming is setting your pricing high relative to major competitors and is often used if the pricing objective is to maximise profitability. Market penetration is setting your pricing low relative to major competitors and is often used to maximise market share. Finally competitor matching is setting your pricing at a similar level to the competition and is often used to maximise customer retention.

Market skimming

If you’re the only product in the market or have a highly differentiated proposition but can only supply a small proportion of the market then a marketing skimming strategy is often best. This allows you to maximise profitability and use your high pricing to limit demand. However over time competitors will enter the market and undercut you. One strategy to defend a high-end proposition is to broaden your portfolio to include offers that also address the lower end of the market. Versioning, discussed in the Pricing Structures article, is a great example of this.

Market penetration

Companies usually adopt a penetration pricing approach because they want to grab market share. However penetration pricing requires an iron-grip on costs and efficiency as it is often only with economies of scale that the product becomes profitable.

Another challenge with penetration pricing is its sustainability; customers buying on price are the most fickle. If a lower-priced competitor with a better operational model comes along (or one that is more desperate) your customers may rapidly churn to them. Japanese companies, in the 1980s, took a penetration pricing approach in hi-tech electronics until they were undercut by Korean and Chinese businesses. At this point their business model had to change to focus on quality, differentiation and brand development.

Competitor matching

This pricing strategy results in propositions that are priced at similar levels to the competition. This strategy can be most appropriate where markets are only growing slowly or not at all. In these mature markets any change to pricing can be easily matched by competitors resulting in minor shifts in market share and profit reduction for all. A competitor matching pricing strategy is said to result in a more stable market for everyone. This pricing strategy may also be best for second tier competitors who can align with a strong market leader; for example, second tier competitors without a significantly differentiated offer will price slightly below the leader.

Each of these three pricing strategies has their merits and choosing the appropriate one depends on your pricing objectives, where your product is in its lifecycle and how differentiated your proposition is. Pricing strategy usually evolves during the lifecycle of a product category with a tendency toward the average price as markets mature and move into decline.

Other pricing strategies and structures

These include, up-selling where customers are persuaded to buy a more advanced option, cross-selling where customers are persuaded to buy additional products in the portfolio (eg. bundling) and segment-based pricing where pricing is varied based on different customer segments (eg. students, employed, old-age pensioners).

Telecoms operators in mature markets often use price complexity to make it difficult for customers to compare offerings with the competition. Supermarkets often use a promotional pricing strategy with a constant set of special offers and discounts.

Cost plus pricing is where an ‘open-book’ approach reveals a supplier’s costs, and a fixed profit margin is agreed with the customer. Although rare, it is seen in some professional services and government contracts.