There are actually three Stanley Cups

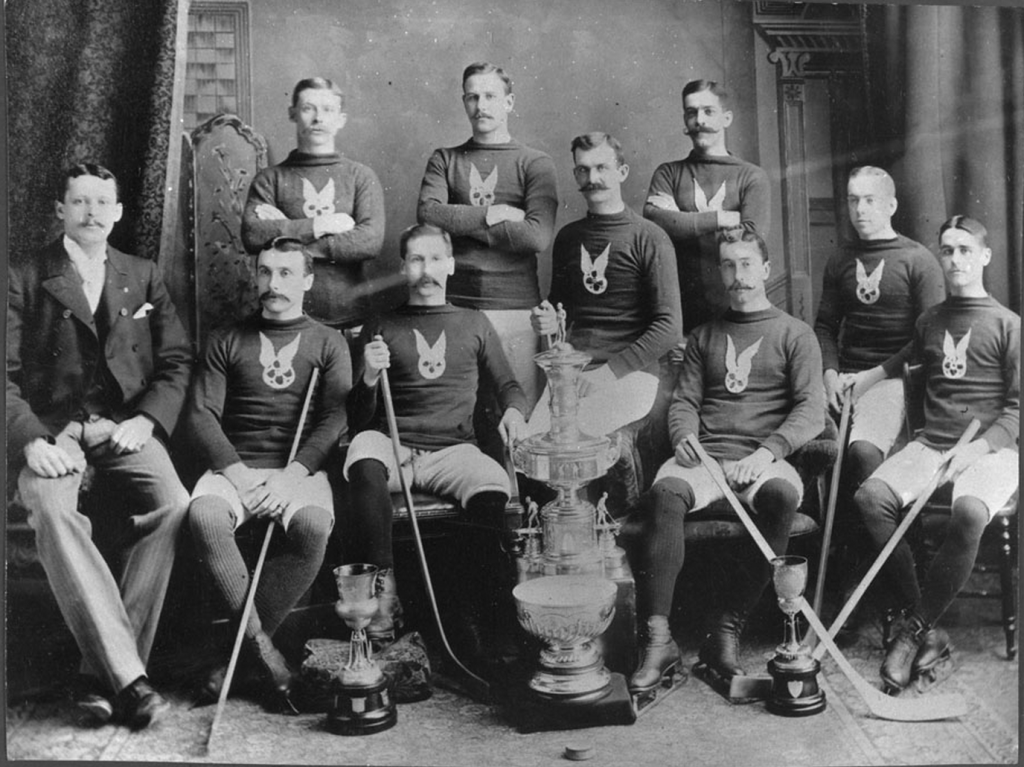

Stanley’s original Cup from 1892, known as the “Dominion Hockey Challenge Cup” (above), was awarded until 1970, and is now on display in the Vault Room at the Hockey Hall of Fame in Toronto.

In 1963, NHL president Clarence Campbell believed that the original Cup had become too brittle to give to championship teams, so the “Presentation Cup” was created and is the well-known trophy awarded today. (Skeptics can authenticate the Presentation Cup by noting the Hockey Hall of Fame seal on the bottom.)

The final Cup is a replica of the Presentation Cup, which was created in 1993 by Montreal silversmith Louise St. Jacques and is used as a stand-in at the Hall of Fame when the Presentation Cup isn’t available.

History

Hockey has been played for longer than any of us has been alive, but we can’t tell you exactly when it was invented, or by whom, because no one really knows for sure. We do have some idea of how it got started, however, and we can describe the ways the game has grown and changed over the years. Once a relatively obscure recreation for people who lived in the north country, hockey is now played all over the world and has become one of the most popular winter sports. Frankly, we don’t know what we’d do without it, and millions of other people feel the same way.What is Hockey?

The Origins of the Game

Most historians place the roots of hockey in the chilly climes of northern Europe, specifically Great Britain and France, where field hockey was a popular summer sport more than 500 years ago. When the ponds and lakes froze in winter, it was not unusual for the athletes who fancied that sport to play a version of it on ice.

An ice game known as kolven was popular in Holland in the 17th century, and later on the game really took hold in England. In his book, Fischler’s Illustrated History of Hockey, veteran hockey journalist and broadcaster Stan Fischler writes about a rudimentary version of the sport becoming popular in the English marshland community of Bury Fen in the 1820s.

The game, he explains, was called bandy, and the local players used to scramble around the town’s frozen meadowlands, swatting a wooden or cork ball, known as a kit or cat, with wooden sticks made from the branches of local willow trees. Articles in London newspapers around that time mention increasing interest in the sport, which many observers believe got its name from the French word hoquet, which means “shepherd’s crook” or “bent stick.” A number of writers thought this game should be forbidden because it was so disruptive to people out for a leisurely winter skate.

Hockey Comes to North America

Not surprisingly, the earliest North American games were played in Canada. British soldiers stationed in Halifax, Nova Scotia, were reported to have organized contests on frozen ponds in and around that city in the 1870s, and about that same time in Montreal students from McGill University began facing off against each other in a downtown ice rink. The continent’s first hockey league was said to have been launched in Kingston, Ontario, in 1885, and it included four teams.

Hockey became so popular that games were soon being played on a regular basis between clubs from Toronto, Ottawa, and Montreal. The English Governor General of Canada, Lord Stanley of Preston, was so impressed that in 1892 he bought a silver bowl with an interior gold finish and decreed that it be given each year to the best amateur team in Canada. That trophy, of course, has come to be known as the Stanley Cup and is awarded today to the franchise that wins the National Hockey League playoffs.

When hockey was first played in Canada, the teams had nine men per side. But by the time the Stanley Cup was introduced, it was a seven-man game. The change came about accidentally in the late 1880s after a club playing in the Montreal Winter Carnival showed up two men short, and its opponent agreed to drop the same number of players on its team to even the match. In time, players began to prefer the smaller squad, and it wasn’t long before that number became the standard for the sport. Each team featured one goaltender, three forwards, two defensemen, and a rover, who had the option of moving up ice on the attack or falling back to defend his goal.

The Rise of Professional Hockey

Hockey was a strictly amateur affair until 1904, when the first professional league was created – oddly enough in the United States. Known as the International Pro Hockey League, it was based in the iron-mining region of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. That folded in 1907, but then an even bigger league emerged three years later, the National Hockey Association (NHA). And shortly after that came the Pacific Coast League (PCL). In 1914, a transcontinental championship series was arranged between the two, with the winner getting the coveted cup of Lord Stanley. World War I threw the entire hockey establishment into disarray, and the men running the NHA decided to suspend operations.

But after the war, the hockey powers that be decided to start a whole new organization that would be known as the National Hockey League (NHL). At its inception, the NHL boasted five franchises- the Montreal Canadiens, the Montreal Wanderers, the Ottawa Senators, the Quebec Bulldogs, and the Toronto Arenas. The league’s first game was held Dec. 19, 1917. The clubs played a 22-game schedule and, picking up on a rule change instituted by the old NHA, dropped the rover and employed only six players on a side. Toronto finished that first season on top, and in March 1918 met the Pacific Coast League champion Vancouver Millionaires for the Stanley Cup. Toronto won, three games to two. Eventually the PCL folded, and at the start of the 1926 season, the NHL, which at that point had ten teams, divided into two divisions and took control of the Stanley Cup.

What They Wore – and Didn’t Wear – In Years Past

It’s remarkable how little equipment the hockey players of the past wore and how rudimentary the gear they did have truly was. In the beginning, skates consisted of blades that were attached to shoes, and sticks were made from tree branches. The first goalie shin and knee pads had originally been designed for cricket. The quality of the gear progressed over the years, with true hockey skates being made and players wearing protective gloves. Shin guards eventually came into being, but many times they didn’t do much to soften the blow of a puck or stick, and players were known to stuff newspaper or magazines behind them for extra protection.

For many years the blades on sticks were completely straight, but New York Rangers star Andy Bathgate began experimenting with a curve in the late 1950s. During a European tour of Ranger and Blackhawk players, Bathgate showed his innovation to Bobby Hull and Stan Mikita, and they began playing with one themselves. And it wasn’t long before most NHL players had done the same thing.

Amazingly, goalies played without masks until 1959, when Jacques Plante wore face protection at a game in the old Madison Square Garden after he had taken a puck in the cheekbone from Andy Bathgate. Plante’s coach, Toe Blake, pressured him to shed the mask later on, and he did for a while. But he started wearing a mask again the following spring, and other goaltenders eventually followed suit. But it wasn’t until 1973 that an NHL netminder (journeyman Andy Brown) appeared in a game without a mask for the last time.

It’s also surprising to think that players didn’t begin wearing helmets with any sort of regularity until the early 1970s; prior to that the only people who wore them did so mostly because they were recovering from a head injury, or, as was the case of one former Chicago Blackhawk forward, because they were embarrassed about being bald. (No, it wasn’t Bobby Hull.) The League passed a rule prior to the start of the 1979-80 season decreeing that anyone who came into the NHL from that point on had to wear a helmet. By the early 1990s there were only a few players left who went bareheaded, and the last one to do so was Craig MacTavish, who retired after the 1996-97 season.

Source: From Hockey For Dummies, by John Davidson with John Steinbreder. Copyright 1997 IDG Books Worldwide, Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduced here by permission of the publisher. For Dummies is a registered trademark of IDG Books Worldwide, Inc.