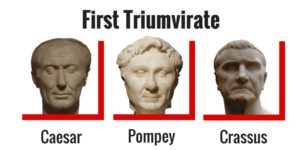

The First Triumvirate is the name historians give to the unofficial political alliance of Gaius Julius Caesar, Marcus Licinius Crassus, and Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (“Pompey the Great”). Unlike the somewhat less famous “Second Triumvirate”, the First Triumvirate had no official status whatever — its overwhelming power in the Roman state was strictly unofficial influence –, and was in fact kept secret for some time as part of the political machinations of the Triumviri themselves.

Crassus and Pompey had been colleagues (they had always despised each other) in the consulate for 70 BC, when they had legislated the full restoration of the tribunate of the people (the dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla had stripped the office of all its powers except the ius auxiliandi, the right to rescue a plebeian from the clutches of a patrician magistrate). However, since that time, the two men had entertained considerable antipathy for one another, each believing the other to have gone out of his way to increase his own reputation at his colleague’s expense.

Caesar contrived to reconcile the two men, and then combined their clout with his own to have himself elected consul in 59 BC; he and Crassus were already the best of friends, and he solidified his alliance with Pompey by giving him his own daughter Iulia Caesaris in marriage. The alliance combined Caesar’s enormous popularity and legal reputation with Crassus’s fantastic wealth and influence within the plutocratic Ordo Equester and Pompey’s equally spectacular wealth and military reputation.

The Triumvirate was kept secret until the Senate obstructed Caesar’s proposed agrarian law establishing colonies of Roman citizens and distributing portions of the public lands (ager publicus). He promptly brought the law before the Council of the People in a speech which found him flanked by Crassus and Pompey, thus revealing the alliance. Caesar’s agrarian law was carried through, and the Triumviri then proceeded to allow the demagogue Publius Clodius Pulcher’s election as tribune of the people, successfully ridding themselves both of Marcus Tullius Cicero and Marcus Porcius Cato, both adamant opponents of the Triumviri.

The Triumvirate proceeded to make further arrangements for itself. Caesar was awarded the government as proconsul of both Gauls (Gallia Cisalpina and Gallia Transalpina) and of Illyricum, with command of four legions, for five years; Caesar’s new father-in-law, Lucius Calpurnius Piso, was made consul for 58 BC, and Pompey and Crassus shared a second consulate in 55 BC. Pompey and Crassus then extended Caesar’s proconsular government in the Gauls for another five years and secured for themselves as proconsuls the government of both Spains (Hispania Citerior and Hispania Ulterior) and of Syria, respectively, for five-year terms.

The alliance had allowed the Triumviri to dominate Roman politics completely, but it could not last indefinitely in light of the ambitions, egos, and jealousies of the three; Caesar and Crassus were implicitly hand-in-glove, but Pompey disliked Crassus and grew increasingly envious of Caesar’s spectacular successes in the Gallic War, whereby he annexed the entirety of modern France to Rome. Julia Caesaris’s death during childbirth and Crassus’s ignominious defeat and death at Carrhae at the hands of the Parthians in 53 BC seriously undermined the alliance.

Pompey remained in Rome — he governed his Spanish provinces through lieutenants — and remained in virtual control of the city throughout that time. He gradually drifted further and further from his alliance with Caesar, eventually marrying the daughter of Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius Cornelianus Scipio Nasica, one of the boni (“Good Men”), an archconservative faction of the Senate steadfastly opposed to Caesar. Pompey was elected consul without colleague in 52 BC, and took part in the politicking which led to Caesar’s crossing of the Rubicon in 49 BC, starting the Civil War. Pompey was made commander-in-chief of the war by the Senate, and was defeated by his former ally Caesar at Pharsalus. Pompey’s subsequent murder in Egypt in an inept political intrigue left Caesar sole master of the Roman world.

Janet Rogers recently put together a resource you might like. It’s a detailed, 8,000-word guide on the 100 best things to do in France that is packed with tips and advice.

Her top three are:

1. The Eiffel Tower

2. Arc de Triomphe

3. The Louvre

Here is the link to the article: https://www.your-rv-lifestyle.com/things-to-do-in-france.html

Source and read more . . .