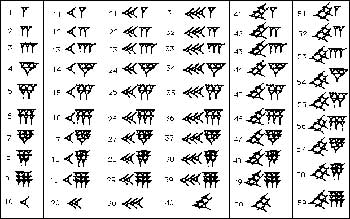

Here are the 59 symbols built from these two symbols

Often when told that the Babylonian number system was base 60 people's first reaction is: what a lot of special number symbols they must have had to learn. Now of course this comment is based on knowledge of our own decimal system which is a positional system with nine special symbols and a zero symbol to denote an empty place. However, rather than have to learn 10 symbols as we do to use our decimal numbers, the Babylonians only had to learn two symbols to produce their base 60 positional system.

Now although the Babylonian system was a positional base 60 system, it had some vestiges of a base 10 system within it. This is because the 59 numbers, which go into one of the places of the system, were built from a 'unit' symbol and a 'ten' symbol.

Now there is a potential problem with the system. Since two is represented by two characters each representing one unit, and 61 is represented by the one character for a unit in the first place and a second identical character for a unit in the second place then the Babylonian sexagesimal numbers 1,1 and 2 have essentially the same representation. However, this was not really a problem since the spacing of the characters allowed one to tell the difference. In the symbol for 2 the two characters representing the unit touch each other and become a single symbol. In the number 1,1 there is a space between them.

A much more serious problem was the fact that there was no zero to put into an empty position. The numbers sexagesimal numbers 1 and 1,0, namely 1 and 60 in decimals, had exactly the same representation and now there was no way that spacing could help. The context made it clear, and in fact despite this appearing very unsatisfactory, it could not have been found so by the Babylonians. How do we know this? Well if they had really found that the system presented them with real ambiguities they would have solved the problem – there is little doubt that they had the skills to come up with a solution had the system been unworkable. Perhaps we should mention here that later Babylonian civilisations did invent a symbol to indicate an empty place so the lack of a zero could not have been totally satisfactory to them.

An empty place in the middle of a number likewise gave them problems. Although not a very serious comment, perhaps it is worth remarking that if we assume that all our decimal digits are equally likely in a number then there is a one in ten chance of an empty place while for the Babylonians with their sexagesimal system there was a one in sixty chance. Returning to empty places in the middle of numbers we can look at actual examples where this happens.

Here is an example from a cuneiform tablet (actually AO 17264 in the Louvre collection in Paris) in which the calculation to square 147 is carried out. In sexagesimal 147 = 2,27 and squaring gives the number 21609 = 6,0,9.

Excerpt from:

Article by: J J O'Connor and E F Robertson

December 2000

MacTutor History of Mathematics

[http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/HistTopics/Babylonian_numerals.html]