“… It was here that the Olympian gods spoke to mortal men through the use of a priesthood, which interpreted the trance-induced utterances of the Pythoness or Pythia. She was a middle-aged woman who sat on a copper-and-gold tripod, or, much earlier, on the “rock of the sibyl” (medium), and crouched over a fire while inhaling the smoke of burning laurel leaves, barley, marijuana, and oil, until a sufficient intoxication for her prophecies had been produced.”

“… It was here that the Olympian gods spoke to mortal men through the use of a priesthood, which interpreted the trance-induced utterances of the Pythoness or Pythia. She was a middle-aged woman who sat on a copper-and-gold tripod, or, much earlier, on the “rock of the sibyl” (medium), and crouched over a fire while inhaling the smoke of burning laurel leaves, barley, marijuana, and oil, until a sufficient intoxication for her prophecies had been produced.”

FROM ANCIENT EGYPT TO GREECE: TIS THINE OWN APOLLO REIGNS

According to the Greeks, the greatest outcome of the love affair between Zeus and Leto was the birth of the most beloved of the oracle gods—Apollo. More than any other god in ancient history, Apollo represented the passion for prophetic inquiry among the nations. Though mostly associated with classical Greece, scholars agree that Apollo existed before the Olympian pantheon and some even claim that this entity was first known as Apollo by the Hyperboreans—an ancient and legendary people to the north. Herodotus came to this conclusion and recorded how the Hyperboreans continued in worship of Apollo even after his induction into the Greek pantheon, making an annual pilgrimage to the land of Delos where they participtated in the famous Greek festivals of Apollo. Lycia—a small country in southwest Turkey—also had an early connection with Apollo, where he was known as Lykeios, which some have joined to the Greek Lykos or ‘wolf’, thus making one of his ancient titles, “the wolf slayer.”

Apollo, with his twin sister Artemis, was said by the Greeks to have been born in the land of Delos—the children of Zeus (Jupiter) and of the Titaness Leto. While an important oracle existed there and played a role in the festivals of the god, it was the famous oracle at Delphi that became the celebrated mouthpiece of the Olympian. Located on the mainland of Greece, the omphalos of Delphi (the stone which the Greeks believed marked the center of the earth) can still be found among the ruins of Apollo’s Delphic temple. So important was Apollo’s oracle at Delphi that wherever Hellenism existed, its citizens and kings, including some from as far away as Spain, ordered their lives, colonies, and wars, by its sacred communications.

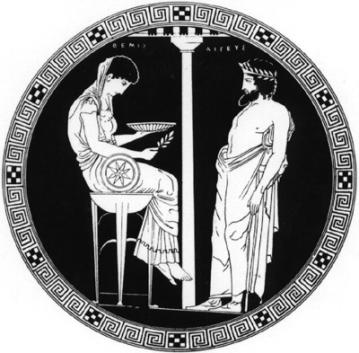

It was here that the Olympian gods spoke to mortal men through the use of a priesthood, which interpreted the trance-induced utterances of the Pythoness or Pythia. She was a middle-aged woman who sat on a copper-and-gold tripod, or, much earlier, on the “rock of the sibyl” (medium), and crouched over a fire while inhaling the smoke of burning laurel leaves, barley, marijuana, and oil, until a sufficient intoxication for her prophecies had been produced.

It was here that the Olympian gods spoke to mortal men through the use of a priesthood, which interpreted the trance-induced utterances of the Pythoness or Pythia. She was a middle-aged woman who sat on a copper-and-gold tripod, or, much earlier, on the “rock of the sibyl” (medium), and crouched over a fire while inhaling the smoke of burning laurel leaves, barley, marijuana, and oil, until a sufficient intoxication for her prophecies had been produced.

While the use of the laurel leaves may have referred to the nymph Daphne (Greek for laurel), who escaped from Apollo’s sexual intentions by transforming herself into a laurel tree, the leaves also served the practical purpose of supplying the necessary amounts of hydrocyanic acid and complex alkaloids which, when combined with hemp, created powerful hallucinogenic visions. An alternative version of the Oracle myth claims that the Pythia sat over a fissure breathing in magic vapors that rose up from a deep crevice within the earth. The vapors “became magic” as they were mingled with the “smells” of the rotting carcass of the dragon Python, which had been slain and thrown down into the crevice by Apollo as a youth.

In either case, it was under the influence of such ‘forces’ that the Pythia prophesied in an unfamiliar voice thought to be that of Apollo himself. During the pythian trance the medium’s personality often changed, becoming melancholic, defiant, or even animal-like, exhibiting a psychosis that may have been the source of the werewolf myth, or lycanthropy, as the Pythia reacted to an encounter with Apollo/Lykeios—the wolf god. Delphic “women of python” prophesied in this way for nearly a thousand years and were considered to be a vital part of the pagan order and local economy of every Hellenistic community.

This adds to the mystery of adoption of the Pythians and Sibyls by certain quarters of Christianity as “vessels of truth.” These women, whose lives were dedicated to channeling from frenzied lips the messages of gods and goddesses, turn up especially in Catholic art, from altars to illustrated books and even upon the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, where five Sibyls join the Old Testament prophets in places of sacred honor. The Cumaean Sibyl (also known as Amalthaea), whose prophecy about the return of the god Apollo is encoded in the Great Seal of the United States, was the oldest of the Sibyls and the seer of the Underworld who in the Aeneid gave Aeneas a tour of the infernal region.

Whether by trickery or occult power, the prophecies of the Sibyls were sometimes amazingly accurate. The Greek historian, Herodotus (considered the father of history), recorded an interesting example of this. Croesus, the king of Lydia, had expressed doubt regarding the accuracy of Apollo’s Oracle at Delphi. To test the oracle, Croesus sent messengers to inquire of the Pythian prophetess as to what he, the king, was doing on a certain day. The priestess surprised the king’s messengers by visualizing the question, and by formulating the answer, before they arrived. A portion of the historian’s account says:

…the moment that the Lydians (the messengers of Croesus) entered the sanctuary, and before they put their questions, the Pythoness thus answered them in hexameter verse: “…Lo! on my sense there striketh the smell of a shell-covered tortoise, Boiling now on a fire, with the flesh of a lamb, in a cauldron. Brass is the vessel below, and brass the cover above it.” These words the Lydians wrote down at the mouth of the Pythoness as she prophesied, and then set off on their return to Sardis….[when] Croesus undid the rolls….[he] instantly made an act of adoration… declaring that the Delphic was the only really oracular shrine…. For on the departure of his messengers he had set himself to think what was most impossible for any one to conceive of his doing, and then, waiting till the day agreed on came, he acted as he had determined. He took a tortoise and a lamb, and cutting them in pieces with his own hands, boiled them together in a brazen cauldron, covered over with a lid which was also of brass (Herodotus, book 1: 47).

…the moment that the Lydians (the messengers of Croesus) entered the sanctuary, and before they put their questions, the Pythoness thus answered them in hexameter verse: “…Lo! on my sense there striketh the smell of a shell-covered tortoise, Boiling now on a fire, with the flesh of a lamb, in a cauldron. Brass is the vessel below, and brass the cover above it.” These words the Lydians wrote down at the mouth of the Pythoness as she prophesied, and then set off on their return to Sardis….[when] Croesus undid the rolls….[he] instantly made an act of adoration… declaring that the Delphic was the only really oracular shrine…. For on the departure of his messengers he had set himself to think what was most impossible for any one to conceive of his doing, and then, waiting till the day agreed on came, he acted as he had determined. He took a tortoise and a lamb, and cutting them in pieces with his own hands, boiled them together in a brazen cauldron, covered over with a lid which was also of brass (Herodotus, book 1: 47).

Another interesting example of spiritual insight by an Apollonian Sibyl is found in the New Testament Book of Acts. Here the demonic resource that energized the Sibyls is revealed.

And it came to pass, as we went to prayer, a certain damsel possessed with a spirit of divination [of python, a seeress of Delphi] met us, which brought her masters much gain by soothsaying: The same followed Paul and us, and cried, saying, These men are the servants of the most high God, which shew unto us the way of salvation. And this did she many days. But Paul, being grieved, turned and said to the spirit, I command thee in the name of Jesus Christ to come out of her. And he came out the same hour. And when her masters saw that the hope of their gains was gone, they caught Paul and Silas… And brought them to the magistrates, saying, These men, being Jews, do exceedingly trouble our city. (Acts 16:16-20)

The story in Acts is interesting because it illustrates the level of culture and economy that had been built around the oracle worship of Apollo. It cost the average Athenian more than two days’ wages for an oracular inquiry, and the average cost to a lawmaker or military official seeking important State information was charged at ten times that rate. This is why, in some ways, the action of the woman in the book of Acts is difficult to understand. She undoubtedly grasped the damage Paul’s preaching could do to her industry. Furthermore, the Pythia of Delphi had a historically unfriendly relationship with the Jews and was considered a pawn of demonic power. Quoting again from my first book Spiritual Warfare—The Invisible Invasion, we read:

Delphi with its surrounding area, in which the famous oracle ordained and approved the worship of Asclepius, was earlier known by the name Pytho, a chief city of Phocis. In Greek mythology, Python—the namesake of the city of Pytho—was the great serpent who dwelt in the mountains of Parnassus… In Acts 16:16, the demonic woman who troubled Paul was possessed with a spirit of divination. In Greek this means a spirit of python (a seeress of Delphi, a pythoness)…[and] reflects…the accepted Jewish belief…that the worship of Asclepius [Apollo’s son] and other such idolatries were, as Paul would later articulate in 1 Corinthians 10:20, the worship of demons. [1]

It could be said that the Pythia of Acts 16 simply prophesied the inevitable. That is, the spirit that possessed her knew the time of Apollo’s reign was over for the moment, and that the spread of Christianity would lead to the demise of the Delphic oracle. This is possible as demons are sometimes aware of changing dispensations (compare the pleas of the demons in Matthew 8:29, “…What have we to do with thee, Jesus, thou Son of God? art thou come hither to torment us before the time?”). The last recorded utterance of the oracle at Delphi seems to indicate the spirit of the Olympians understood this. From Man, Myth & Magic, we read:

Apollo….delivered his last oracle in the year 362 AD, to the physician of the Emperor Julian, the Byzantine ruler who tried to restore paganism after Christianity had become the official religion of the Byzantine Empire. ‘Tell the King,’ said the oracle, ‘that the curiously built temple has fallen to the ground, that bright Apollo no longer has a roof over his head, or prophetic laurel, or babbling spring. Yes, even the murmuring water has dried up.’ [2]

Apollo….delivered his last oracle in the year 362 AD, to the physician of the Emperor Julian, the Byzantine ruler who tried to restore paganism after Christianity had become the official religion of the Byzantine Empire. ‘Tell the King,’ said the oracle, ‘that the curiously built temple has fallen to the ground, that bright Apollo no longer has a roof over his head, or prophetic laurel, or babbling spring. Yes, even the murmuring water has dried up.’ [2]

As the oracle at Delphi slowly diminished, the entity Apollo secured his final and most durable ancient characterization through the influence of his favorite son—Asclepius. Beginning at Thessaly and spreading throughout the whole of Asia Minor, the cult of Asclepius—the Greek god of healing and anti-christ archetype—became the chief competitor of early Christianity. Asclepius was even believed by many pagan converts of Christianity to be a living presence who possessed the power of healing. Major shrines were erected to Asclepius at Epidaurus and at Pergamum, and for a long time he enjoyed a strong cult following in Rome where he was known as Aesculapius. Usually depicted in Greek and Roman art carrying a snake wound around a pole, Asclepius was often accompanied by Telesphoros, the Greek god of convalescence. He was credited with healing a variety of incurable diseases, including raising a man from the dead, a miracle which later caused Hades to complain to Zeus who responded by killing Asclepius with a thunderbolt. When Apollo argued that his son had done nothing worthy of death, Zeus repented and restored Asclepius to life; immortalizing him as the god of medicine.

© 2009 Thomas Horn – All Rights Reserved

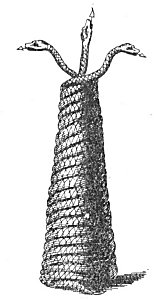

The windings of these serpents formed the base, and the three heads sustained the three feet of the tripod. It is impossible to secure satisfactory information concerning the shape and size of the celebrated Delphian tripod. Theories concerning it are based (in most part) upon small ornamental tripods discovered in various temples.

The windings of these serpents formed the base, and the three heads sustained the three feet of the tripod. It is impossible to secure satisfactory information concerning the shape and size of the celebrated Delphian tripod. Theories concerning it are based (in most part) upon small ornamental tripods discovered in various temples.

From Montfaucon’s Antiquities.

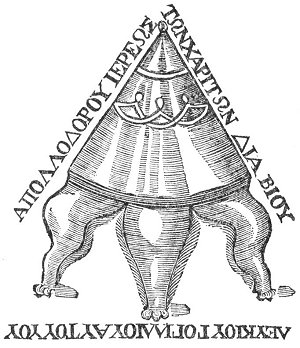

According to Beaumont, this is the most authentic form of the Delphian tripod extant; but as the tripod must have changed considerably during the life of the oracle, hasty conclusions are unwise. In his description of the tripod, Beaumont divides it into four Parts: (1) a frame with three (2), a reverberating basin or bowl set in the frame; (e) a flat plate or table upon which the Pythia sat; and (4) a cone-shaped cover over the table, which completely concealed the priestess and from beneath which her voice sounded forth in weird and hollow tones, Attempts have been made to relate the Delphian tripod with the Jewish Ark of the Covenant.

The frame of three legs was likened to the Ark of the Covenant; the flat plate or table to the Mercy Seat; and the cone-shaped covering to the tent of the Tabernacle itself. This entire conception differs widely from that popularly accepted, but discloses a valuable analogy between Jewish and Greek symbolism.